3 The problem of ‘music books’ – types of sources

3.1 Choirbooks and partbooks

Good news is: If you’re able to work with a music print, you’re also able to work with ‘normal’ printed books. For in music printing, there are some additional problems emerging from the content of the books – music – itself. One must bear in mind here what kind of music was most frequently printed in the Early Modern period: Collections of instrumental music for lute or keyboard instruments, as well as monophonic liturgical prints like Antiphonals and Graduals, was far less popular than polyphonic vocal music of all spiritual and secular genres (masses, motets, madrigals, partsongs, chansons…). In the video, there is one of thousands of examples:

While lute or keyboard music comes with its own problem (which is even feared by some musicologists), a special form of notation called tablature, polyphonic music was not notated in score as we’re used to today, but in individual parts. With the number of voices ranging from 2 to – in extreme cases – 42, printers of music had to plan their prints carefully. Fortunately, they were able to adopt the concept that was also followed in manuscripts: The voices could either be presented in a set of books, each containing one individual part – the so-called partbooks which logically came as a set –, or in the format of a choirbook. Choirbooks were mostly used by professional chapels at courts and in churches. Each voice is given a designated space on the openings, and the notes are structured so that when you turn the page, all the parts are at the same point within the musical text.

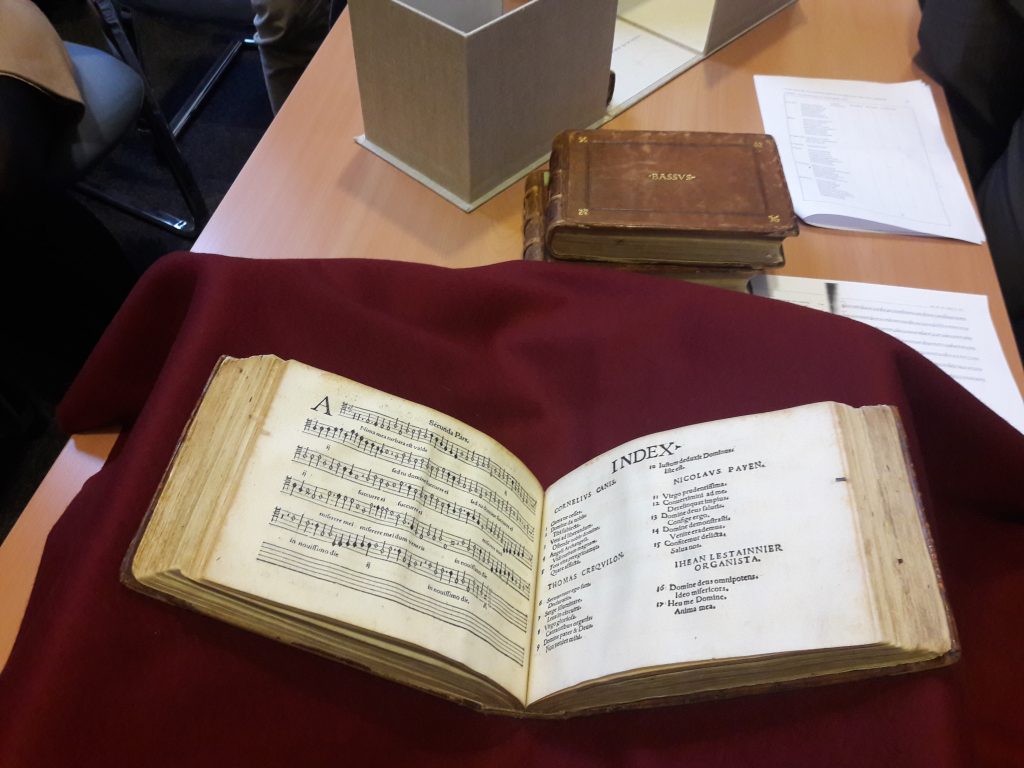

A set of bound partbooks (you can see the other partbooks in the background) at the Bavarian State Library, Munich.

A set of bound partbooks (you can see the other partbooks in the background) at the Bavarian State Library, Munich.

Cantiones selectissimae. Liber primus, Augsburg (Ulhart), 1548.

Munich, Bavarian State Library, 4 Mus.pr. 101.

(Photo: private)

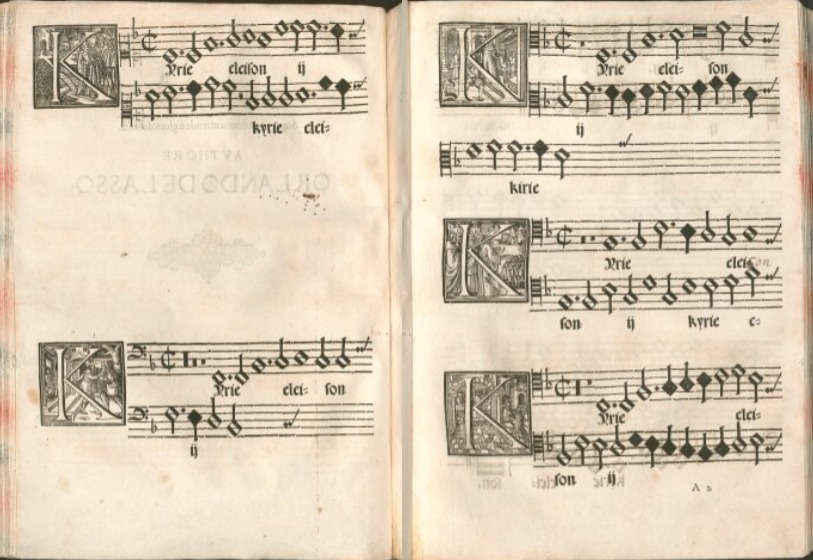

Opening of a Choirbook.

Orlando di Lasso, Patrocinium Musices, Munich (Adam Berg), 1589.

Munich, Bavarian State Library, 2 Mus.pr. 10, fol. 57v-58r.

Schematic representation of the positions of the individual voices in the preceding example.

Schematic representation of the positions of the individual voices in the preceding example.

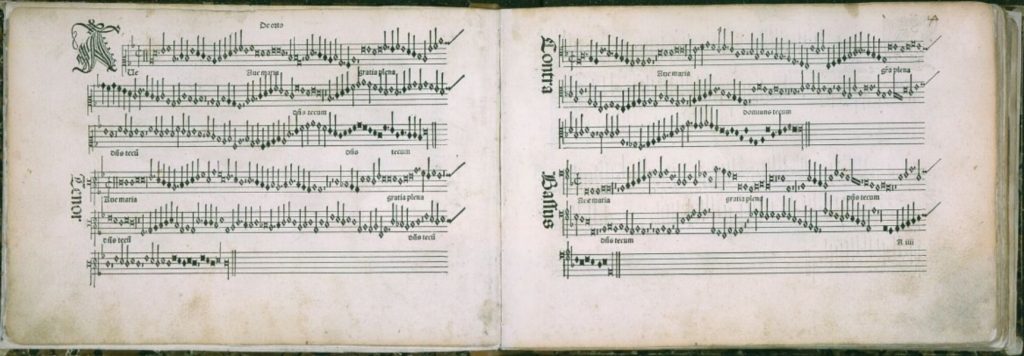

Of course, the layout can be adapted to the number of voices. And: There are different ways to organise the voices in a choirbook. The Patrocinium Musices is an example for the 'Munich choirbook layout', primarily used by the Munich court chapel. You might remember Petrucci's Odhecaton from the first chapter. It's also a choirbook (though the oblong format is rather uncommon for choirbooks), but here, the Bassus and the Contratenor (Alto) can be found on the right page, while Soprano and Tenor are on the left side.

Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, Venice (Ottaviano Petrucci), 1501.

Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, Venice (Ottaviano Petrucci), 1501.

Bologna, Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica, Q. 51, p. 8-9.

Click here to access the full digitized source.