1 The roots and techniques of music printing

1.1 'milestones' of (music) printing

Early printing in China and Korea

In Europe, we associate the beginning of commercial printing with the invention of the printing press with movable type by Johannes Gutenberg. In China, however, woodblock printing had been used since the 5th century, and from the 11th century onwards, printing type made of clay was used. Copper types were invented in Korea as early as around the year 1300.

Gutenberg's printing press

Gutenberg himself learned the printing craft with woodcuts before he started to assemble the respective pages from individual letter punches - printing letters - around 1450. Compared to the woodcut, this had the advantage that the material could be put together again and again to form new texts, which was also a lot faster than making a separate woodcut for each page (which of course also had its advantages if you wanted to reprint the exact same page at a later point in time).

The first music print

Gutenberg’s invention is often considered as the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Early Modern Period. Print was ground-breaking especially for the events of the Reformation: In books and in the format of flyers (like those we know today), information and, of course, opinions could be spread widely – at least within the literate class. During the 16th century, the European market for printed books of all fields grew rapidly. Print has not failed to leave its mark on music culture: Music was printed from the second half of the 15th century onwards; the oldest known music print is a Graduale Romanum from Constance, printed around 1470.

Graduale Romanum, Constance, c. 1470.

Graduale Romanum, Constance, c. 1470.

London, British Library, I.B.15154, fol. 1r.

Click here to access the full digitized source.

Petrucci's method: multiple impression printing

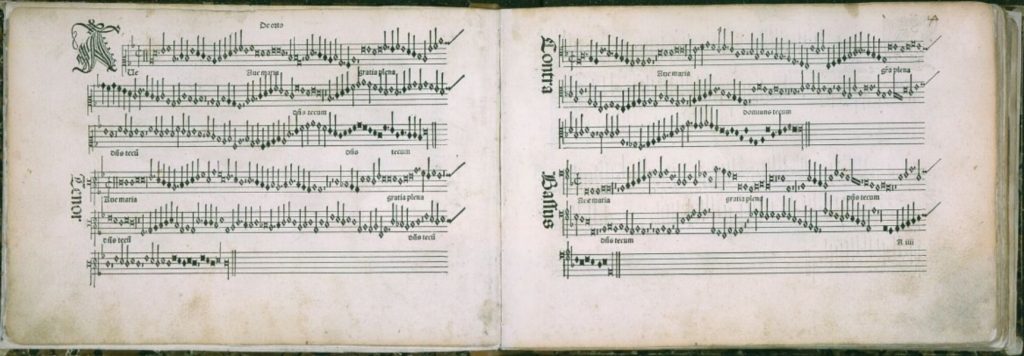

These first music prints, exclusively monophonic liturgical books (like the Graduale), were still woodcut prints – in these early times of printing also known as Incunabula. The next ‘milestone’ of music printing was reached around 50 years after Gutenberg’s invention: The Venetian printer Ottaviano Petrucci started to print music with movable types. But printing music comes with even more problems than printing ‘just’ text: The printer must assemble the notes on their respective staff lines, and with the correct text underlay. Moreover, there are also quite a lot of special characters such as clefs, measures, and accidentals. Petrucci solved this by printing in multiple steps: At first, he printed the staff lines, then the notes including the clefs and measures, and finally the text. Text and notes were realised using movable type. The mixed-genre Harmonice Musices Odhecaton (in three volumes, the first dating as early as 1501) is considered the first polyphonic music book.

Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, Venice (Ottaviano Petrucci), 1501.

Bologna, Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica, Q. 51, p. 8-9.

Click here to access the full digitized source.

Multiple impression printing north of the Alps

Petrucci’s technique led to nearly unrivalled beautiful and neat-looking editions but entailed a problem. To avoid errors, the frames with notes and texts had to be aligned carefully with the already printed staff lines. The Basel printer Gregor Mewes, who also experimented with Petrucci’s technique, failed in this: His Concentus harmonichi (1507) with four masses by Jacob Obrecht is, unfortunately, quite defective. However, his efforts, as well as those of his colleague Erhard Öglin who was somewhat more successful in ‘hitting’ the staff lines, were the first attempts on printing music with moveable type north of the Alps.

Jacob Obrecht, Concentus Harmonichi quattuor missarum, Basel (Mewes), 1507.

Basel, University Library, kk III 23a-d, Tenor fol. 3r.

Click here to access the full digitized source.

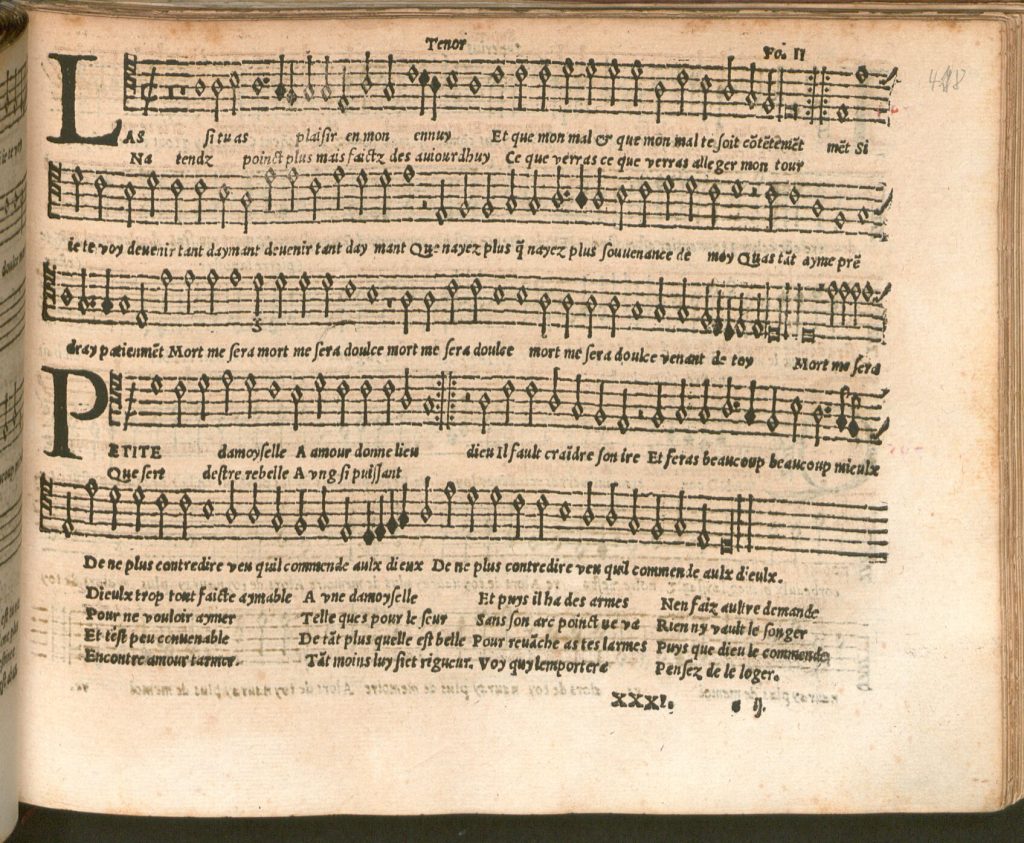

Attaignant's technique: single impression music printing

However, Petrucci’s technology was not really fit for the future as it still took a lot of time to execute the three steps. The technique that was to dominate music printing until the end of the 17th century was that of the Parisian Pierre Attaignant, who designed types in which the staves were already included in 1527/28. Printers from all over Europe – initially in Mainz, Frankfurt, Wittenberg, Augsburg, and Venice – took over this technique.

Clément Janequin, Trente & ungyesme livre contenant XXX. chansons nouvelles à quatre, en deux volumes, Paris (Pierre Attaignant), 1549.

Munich, Bavarian State Library, Rar. 900-1/35, Tenor fol. IIr.

Click here to access the full digitized source.

A consolidated market for printed music

But still, it took around 50 years until a European market for music prints had consolidated. The importance of music printing varied greatly internationally: while some Venetian printers very soon began to specialise in music, it was not economically worthwhile for German printers. The market for Venetian printers was far more international in scope than the German one, who can be, according to John Kmetz (see further readings), considered as a “closed market”. However, Italian, French and German music prints alike were traded on the book fairs of Frankfurt and Leipzig from the second half of the 16th century on.