5. Bilingual and Trilingual Transmission

Inscriptions in Antiquity are usually found in one language, but sometimes they can be in two, or three. Sometimes the inscriptions are merely translations repeating the same information, and other times, the different languages in which the inscription is written provide new meanings to the text. This can be subversive.

Alternatively, different translations also provide different perspectives on Scripture. Consider these two inscriptions which both quote Prov 10:7, one in Latin and Hebrew from Taranto in Italy, and another in Latin, Hebrew, and Greek, from Tortosa in Spain. Both are from 7th-8th century CE.

JIWE I 120 = CIJ I 629 Taranto

[image unavailable]

(A) hic requiescit benememorio An

atolio filio Iusti qui vixit annos

XXXX. sit pax in requie eius

((menorah))

(B) אור זרוע לצדיק ולישר]י-לב[ שמחה

נזכר צדיק לברכה אנתולי

memoria ius

torum ad be

[nedictionem]

(A) (Latin) Here lives Anatoli(us), remembered for the good

son of Justus, who lived

40 years. May here be peace on his rest

((menorah))

(B) (Hebrew) Light is sown for the just man, and joy for the upright of heart

The just man Anatoli(us) is remembered for a blessing.

(Latin) The memory of the just

[with a view] to a

blessing.

The translations are not identical. The Latin assists the Hebrew in (B), adding “the memory of the just for a blessing”. The Hebrew does not mention the father nor the age of the deceased, adding an extra Biblical verse. Epigraphist David Noy has found that the Hebrew quotes both Psalms 97:11 and Proverbs 10:7, and Pieter van der Horst has argued that the version of Prov 10:7 is similar to the LXX translation due to the use of the plural for “the just”. The inclusion of two languages does not only expand the text included on the epitaph, but provides two different perspectives and wishes.

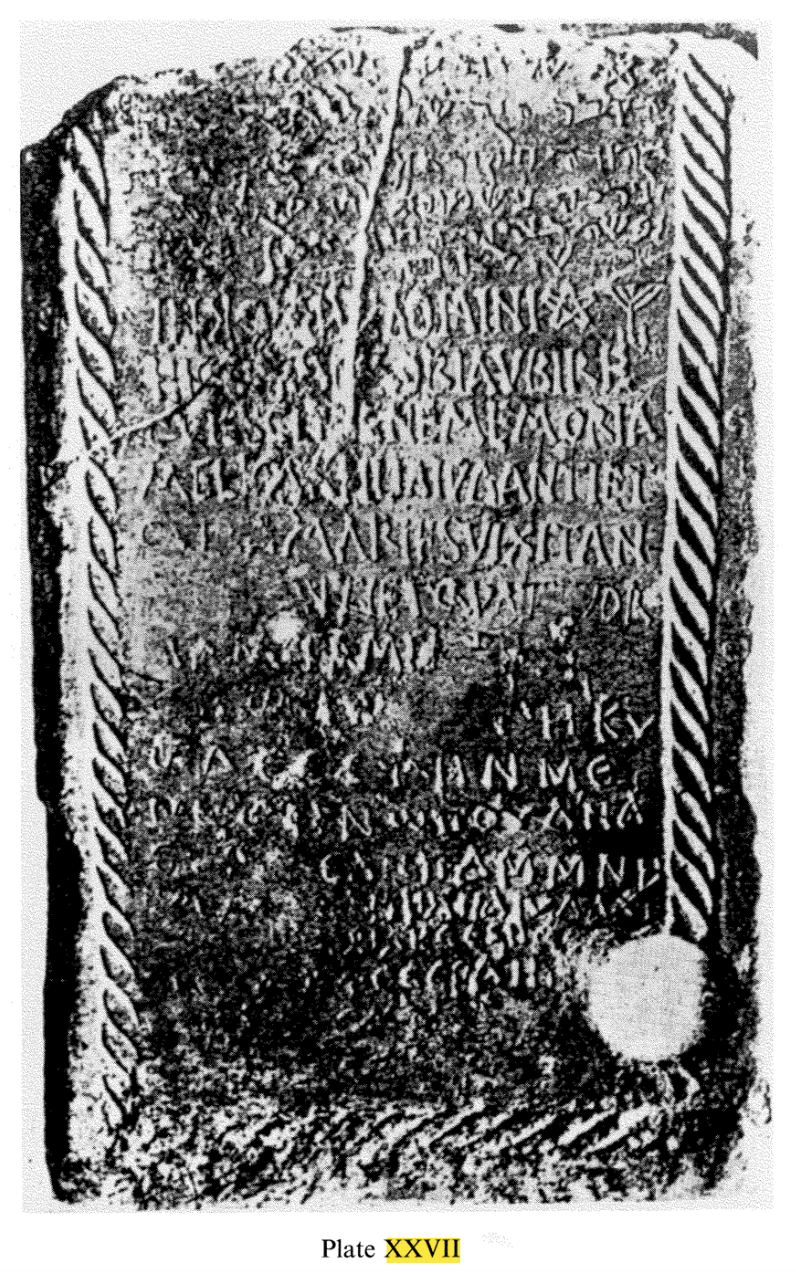

JIWE I 183 = CIJ I 661 (Image: JIWE I) Tortosa

שלום ע(ל) ישראל ((star))

הקבר הזה של מיללאשא ברת ר

יהודה ולקירא מאריס. (זכר) צדקת

לברכה. נישמתה לחיי עולם. תנ(וח)

נפשה בצרור החים. אמן כן (...)

שלום

in nomine Domini ((pentagram)) ((menorah))

hic est m[e]moria ubi re

quiescit benememoria

Meliosa filia Iudanti et

Cura Maries. vixit an

[nos vigi]nti et quattor

cum pace. amen

[ἐν τ]ῷ [ὀν]ώ[μα]τη Κ(υρίο)υ·

ὧδε ἔστην με-

μν[ῖ]ον {ν} ὥπου ἀνά-

π̣[αυετ]αη̣ πάμμνη-

στος Μ̣[ελιώσ]α̣ [φη]ληα Ἰύδαντ-

[ος καὶ κ(υρ)ίας] Μάρες, ζήσ[ασα]

[ἔτη εἴκοσι] τέσερα ἠν {²⁶ἐν}²⁶

[εἰρήνῃ· ἀμήν].

(Hebrew) Peace upon Israel.

This tomb is of Mellasa, daughter of Rabbi Juda and of Lady Maria.

The memory of the just woman is for a blessing.

May her spirit have eternal life!

May her soul rest in the bond of life! Amen so…

Peace.

(Latin) In the name of the Lord.

Here is the memorial in which rests,

remembered for good,

Meliosa the daughter of Juda and

Lady Maria. She lived

twenty-four years,

with peace. Amen.

(Greek) In the name of the Lord.

Here is the

memorial in which

is at rest the all-remembered

Melisoa, daughter of Juda

and Lady Maria. She lived

twenty-four years,

in peace. Amen.

This trilingual inscription, unlike the bilingual inscription we have just looked at, has a similar text in all three languages, with the greatest similarities between the Latin and Greek texts. It introduces the resting place of the individual, and her both parents. The Latin and Greek proclaim the text “in the name of the Lord”; refer to her “memorial”; use similar epithets for “well-remembered”; and both state her age, ending “in/with peace”, and “amen”. The Hebrew text, however, wishes “peace upon Israel”, refers to her “tomb/memorial”, using the common Talmudic term for “grave” (Noy, JIWE I, 251; Jastrow 1903) and her father as “Rabbi”, and most significantly, contains the portion of Prov 10:7 that we have encountered in other inscriptions. The wishes for the deceased’s eternal life and resting of the soul are also unique the Hebrew part of this text. Noy has argued that “Tortosa became a centre of Jewish learning in the 10th and 11th centuries, when it was the home of the poet, grammarian and lexicographer Menahem b. Jacob ibn Saruq and the physician and geographer Ibrahim b. Yaqub” (Noy JIWE I, 253; Beinart 1971). Although this inscription is almost certainly earlier than these two individuals, there is extensive debate about the dating of almost all Jewish inscriptions. As all examples we have encountered in this chapter show, pre-modern Jewish inscriptions tend to state the deceased’s age, but not the date of death, unlike Christian inscriptions, which often use a combination of age and date of death.

Looking once again at all the inscriptions that quote Prov 10:7, which differences are made? Why might they have been made? Why might certain things have been maintained?

JIWE II 307 (LXX) Rome

The memory of the righteous man with praise. [Greek]

JIWE II 276 (LXX & Aquila) Rome

The memory of the righteous man for a blessing, whose eulogies are true. [Greek]

JIWE II 112 (Aquila) Rome

The memory of the righteous one for a blessing. [Greek]

JIWE I 120 Taranto

The righteous man Anatoli(us) is remembered for a blessing. [Hebrew]

The memory of the righteous one for a blessing. [Latin]

JIWE I 183 Tortosa

The memory of the righteous woman is for a blessing. [Hebrew]

To summarise:

- Inscriptions can be bilingual, or even trilingual, but the text in different languages on inscriptions is rarely identical.

- Sometimes texts are transmitted through one language and not another, such as the use of Greek in Biblical Quotations on Jewish inscriptions found in the city of Rome, or Hebrew in Biblical Quotations on Jewish inscriptions found in Western Europe outside Rome.