4. Biblical Quotations on Inscriptions

Sometimes inscriptions don’t just use formulae and set phrases; sometimes inscriptions quote

other texts.

We also do this today, for example:

Sometimes when we quote things in inscriptions, it is less clear what is being referenced.

On Shakespeare’s tomb, it is not fully clear whether in inscription was one he wrote himself; if it was added later, or if he was quoting something else.

Of course, in Jewish and Christian Late Antiquity, the Bible was a very popular source for gathering funerary quotations. However, of the 3500 Jewish inscriptions from Antiquity, only a few had biblical quotations (van der Horst, 67). Christians and Jews, in their ancient Greek funerary inscriptions, also tended to use different quotations. Jews often used 1 Sam 25:29:

“If anyone should rise up to pursue you and to seek your life, the life of my lord shall be bound in the bundle of the living under the care of the Lord your God; but the lives of your enemies he shall sling out as from the hollow of a sling”. (NRSV, 1 Sam 25:29)

For this chapter, however, we will consider another quotation. One that became particularly popular by the Middle Ages was Prov 10:7 (Hebrew Bible Prov 10:9).

“The memory of the righteous is a blessing, but the name of the wicked will rot.” (NRSV, Prov 10:7)

This Biblical quotation is important because it is concerned with memory. Funerary inscriptions are commemorative by nature. They also have explicit references to memory: as shown above, many Latin Christian inscriptions have “bonae memoriae”, “of good memory” on them, and many Latin Jewish inscriptions feature the word “benemerenti”, “well-remembered”. Both “bonae memoriae” and “benemerenti” can be abbreviated to “BM”, and the idea behind these formulae are very similar. The Biblical quotation of Prov 10:7 and the epigraphic formulae of well-remembered/of good memory are making the commemorative functions of inscriptions explicit.

But this quotation is not only important for its commemorative elements. Epigraphist David Noy argues that “the text was important in rabbinic thought: in Gen.R. xlix 1 on Gen. xvii 17-19, R. Isaac cites in in support of his statement: “whoever mentions the name of a righteous man and does not say a blessing for him violates a religious duty of commission”’ (Noy, JIWE I, 157). In other words, this quotation also is a form of authority.

Regarding this biblical verse, because not everyone that wanted to read the Bible spoke Hebrew or Aramaic, the Bible was translated into Greek. Just as not everyone speaks Ancient Greek today, English translations have also been provided(!)

Just as there are many translations of the Bible now, there were also many translations of the Bible in Antiquity. Translations of the Bible are fundamental to believers, as these are understood to be the Word of God, or at least essential instructional words, and so having the correct meaning is important.

Two of the most widespread translations of the Greek Torah/Old Testament were the “Septuagint” (abbreviated here to “LXX”, for the Roman numerals 70), and the translation by Aquila (here just called “Aquila”). The translations of some passages, while similar, are not identical. This is also the case for Prov 10:7:

μνήμη δικαίων μετ ́ ἐγκωμίων

“mnama dikaion met’ egkomion”

memory of the just (man) with praise

Prov 10:7 (LXX)

μνεία δικαίου εἰς εὐλογίαν

“mneia dikaiou eis eulogian”

memory of the just (man) for a blessing

Prov 10:7 (Aquila)

Although they are both very similar, the slight difference in the meanings can be interesting to consider.

How does the meaning change in the case of Prov 10:7?

As this Proverb was popular for funerary inscriptions, and both the LXX and the Aquila translations of the Hebrew Bible were in circulation among the Jewish community of Late Antique Rome, some inscriptions used one version, and others the other.

We will now look at three different examples from the Roman catacombs: One uses the LXX, one uses the Aquila, and one uses both.

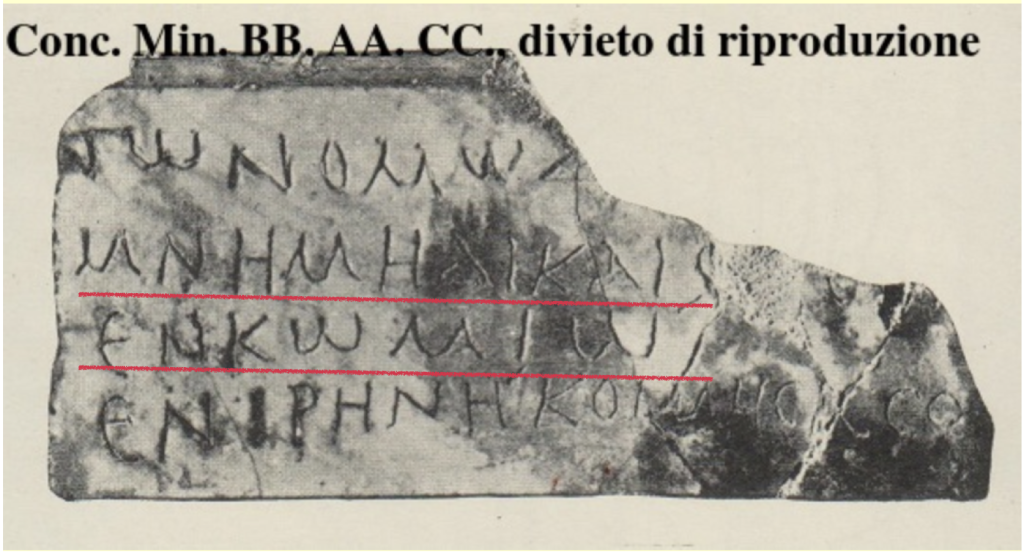

JIWE II 307 (LXX) (Image: EDR)

[+4?+]τῷ νομωδ[ιδασ]-

[κάλῳ]· μνήμη δικαίο̣[υ] σ̣[ὺ]ν̲

ἐνκωμίῳ·

ἐν ἰρήνῃ κοίμησίς σου̲

For ....tus, teacher [or For the teacher] of the law.

The memory of the just man with

praise.

In peace your sleep.

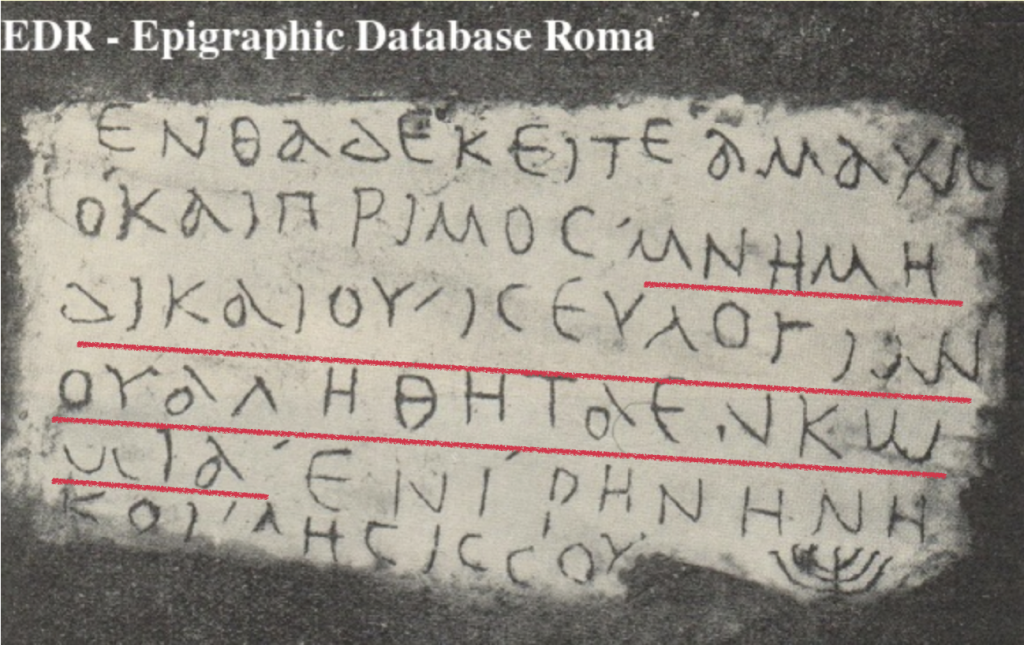

JIWE II 276 (Aquila & LXX) (Image: EDR)

Ἐνθάδε κεῖτε Ἀμάχις

ὁ καὶ Πρῖμος· μνήμη

δικαίου ἰς εὐλογίαν

οὗ ἀληθῆ τὰ ἐνκώ-

μια· ἐν ἰρήνῃ(:εἰρήνῃ) {νη}

κοίμησίς σου ((:menorah))

Here lies Amachius,

who (was) also (called) Primus. The memory

of the just man for a blessing,

whose eulogies are true. In peace

your sleep.

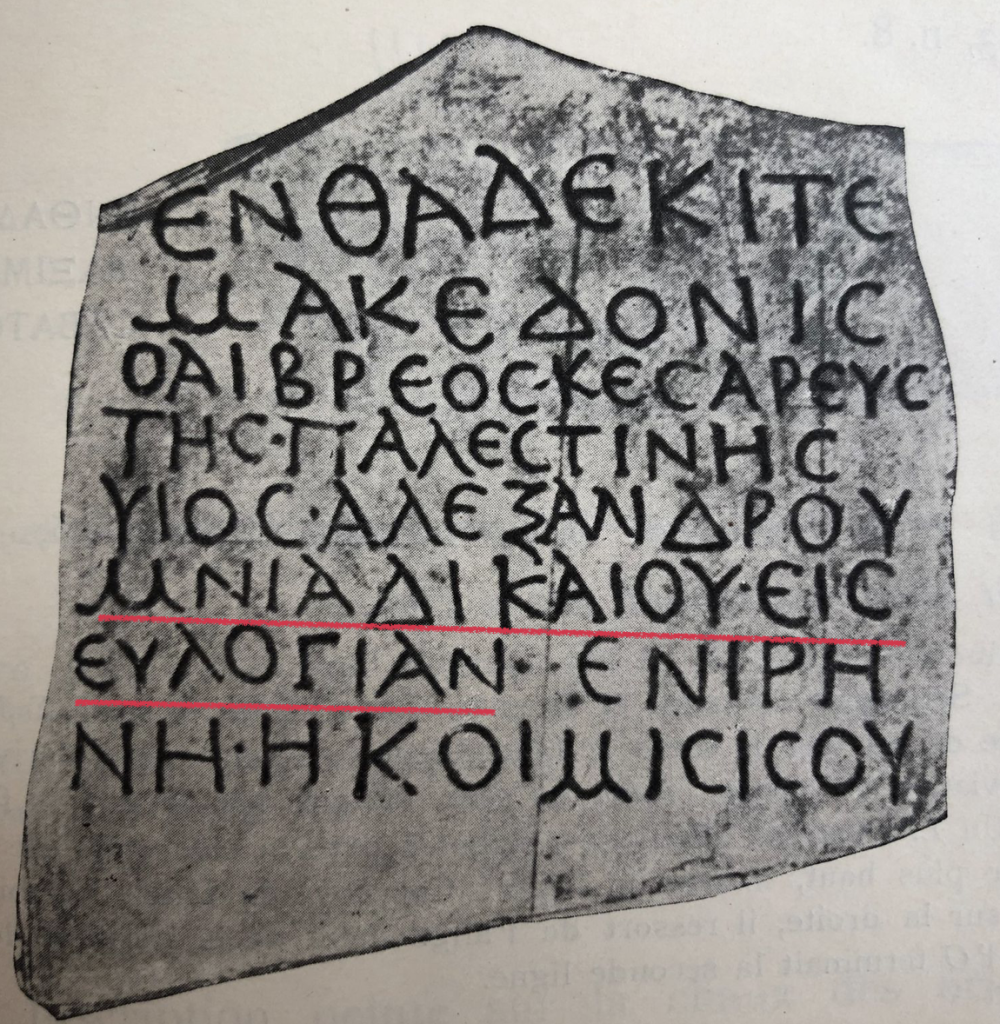

JIWE II 112 (Aquila) (Image: CIJ i 370 (p. 287))

Ἐνθάδε κῖτε

Μακεδόνις

ὁ Αἱβρέος Κεσαρεὺς

τῆς Παλεστίνης,

υἱὸς Ἀλεξάνδρου·

μνία δικαίου εἰς

εὐλογίαν· ἐν ἰρή-

νῃ ἡ κοιμισισου

Here lies

Macedonius

the Hebrew from Caesarea

in Palestine,

son of Alexander.

The memory of the righteous one for

a blessing. In peace

your sleep.

Look at these parts of the transcription.

Prov 10:7 (LXX)

μνήμη δικαίων μετ ́ ἐγκωμίων

“mnama dikaion met’ egkomion”

Prov 10:7 (Aquila)

μνεία δικαίου εἰς εὐλογίαν

“mneia dikaiou eis eulogian”

JIWE II 307 (LXX)

μνήμη δικαίο̣υ σ̣ὺν̲ ἐνκωμίῳ

“mnama dikaiou sun enkomio”

The memory of the righteous man with praise.

JIWE II 276 (LXX & Aquila)

μνήμη δικαίου ἰς εὐλογίαν οὗ ἀληθῆ τὰ ἐνκώμια

“mnama dikaiou is eulogian ou alatha ta enkomia”

The memory of the righteous man for a blessing, whose praises are true.

JIWE II 112 (Aquila)

μνία δικαίου εἰς εὐλογίαν

“mnia dikaiou eis eulogian”

The memory of the righteous man for a blessing.

What is the key word that stays the same?

What stays the same in the translation?

What affect does this have on the text, having the constant of "memory" and "righteous one"?

To summarise:

- Inscriptions may have quotations on them, and in certain contexts, the quotation, or the edition of the text from which it comes, may highlight the cultural influences onto the text.

- Jewish inscriptions of Antiquity in Greek rarely featured Biblical quotations, and when they did, they often used Prov 10:7.

- The translation of the Bible from which the quotation came provides insight into the rabbinic influences on the community in which the individual may have been influenced.