3. Common Elements of Inscriptions II

These same elements of medieval Latin Christian inscriptions also apply to ancient Greek Jewish inscriptions. Where we have looked at medieval Christian inscriptions from south-eastern Gaul as an example, we will now consider ancient Jewish inscriptions from the city of Rome.

The city of Rome has a number of catacombs, which are underground cemeteries. Four of the roughly sixty catacombs of Rome are predominantely Jewish. Watch archaeologist and historian Leonard Rutgers in the catacombs:

There are also Christian catacombs in Rome. Here is an introductory video to one of the Christian catacombs, Saint Callixtus:

While many medieval Latin Christian inscriptions begin with “here in peace rests”, this group of Jewish inscriptions tend to end with the formula “in peace his/her/your sleep” in Greek, “ἐν εἰρήνῃ κοίμησίς σου”. In the next section, we will look at three inscriptions from David Noy’s edition of Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, vol. II (Rome), [henceforth “JIWE II”] nos. 112, 276, 307, which all end in this formula.

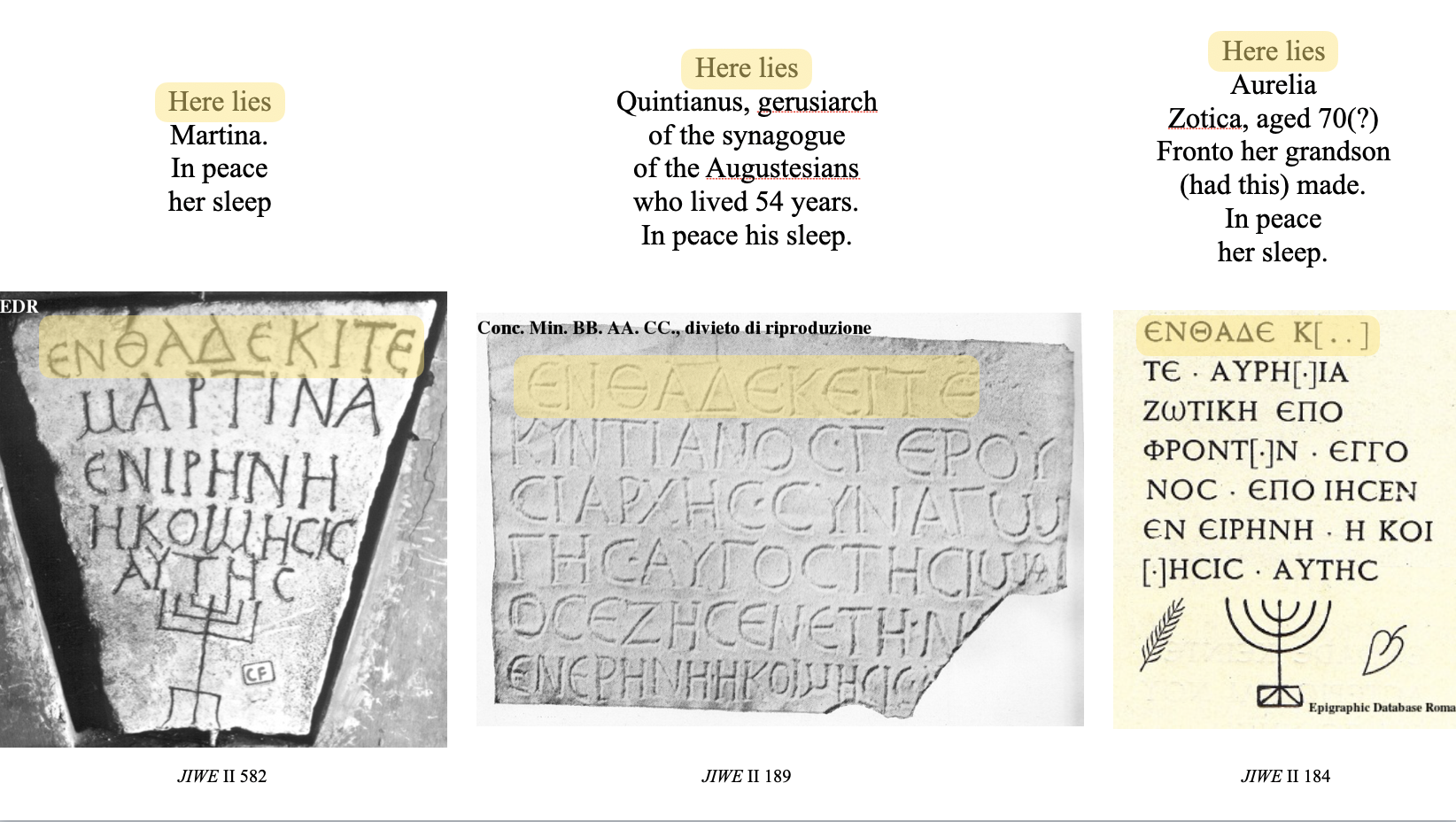

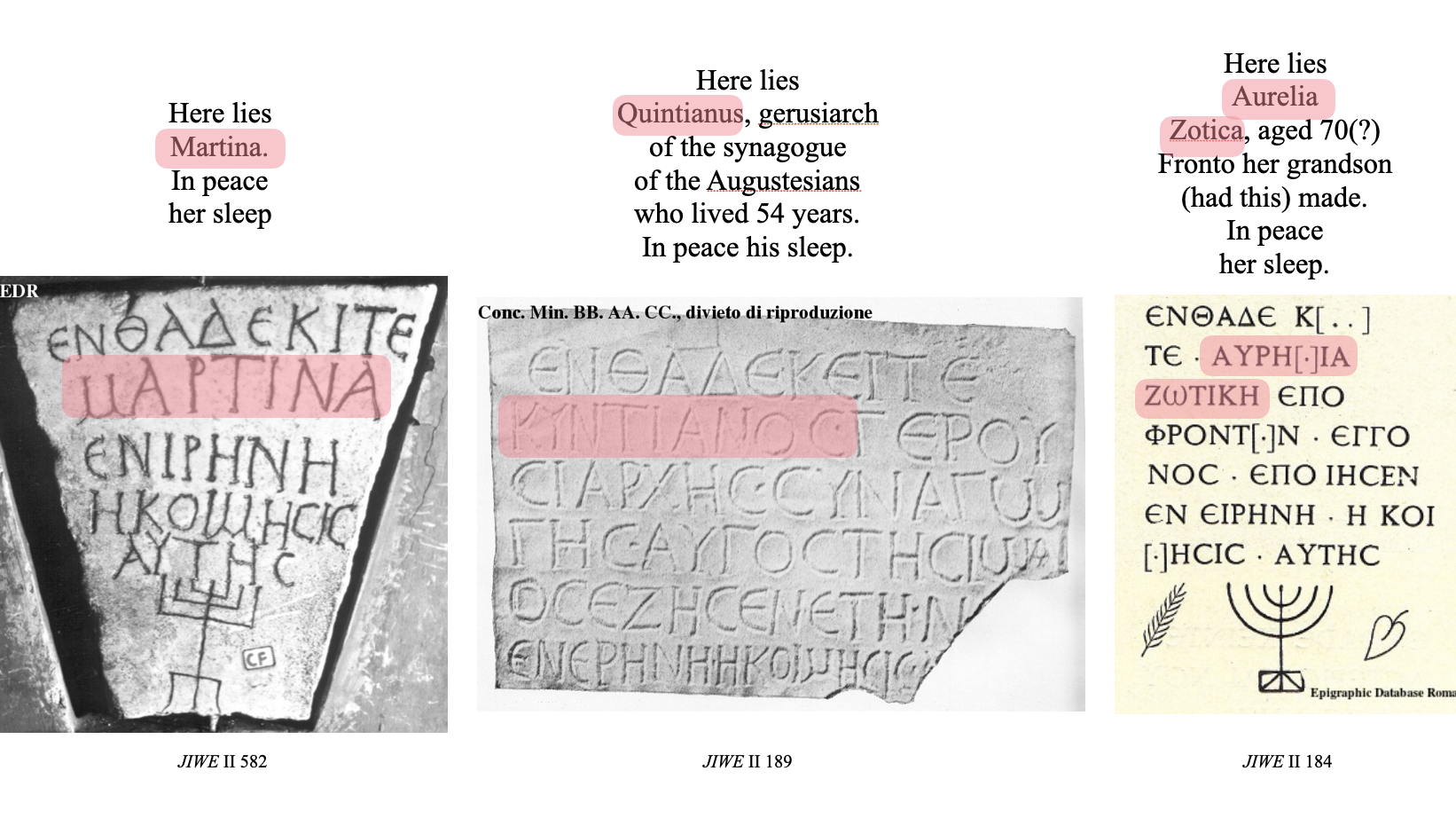

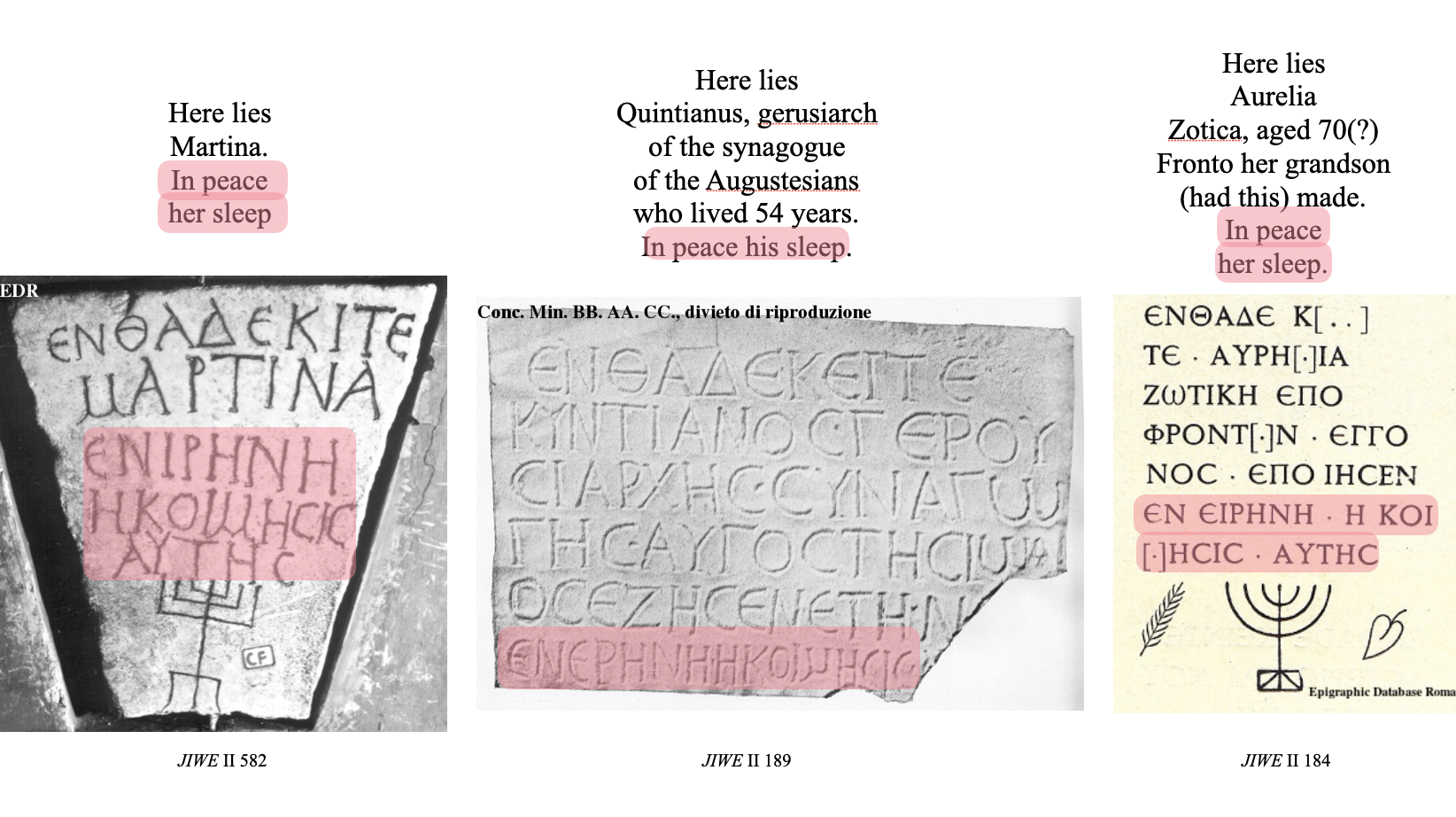

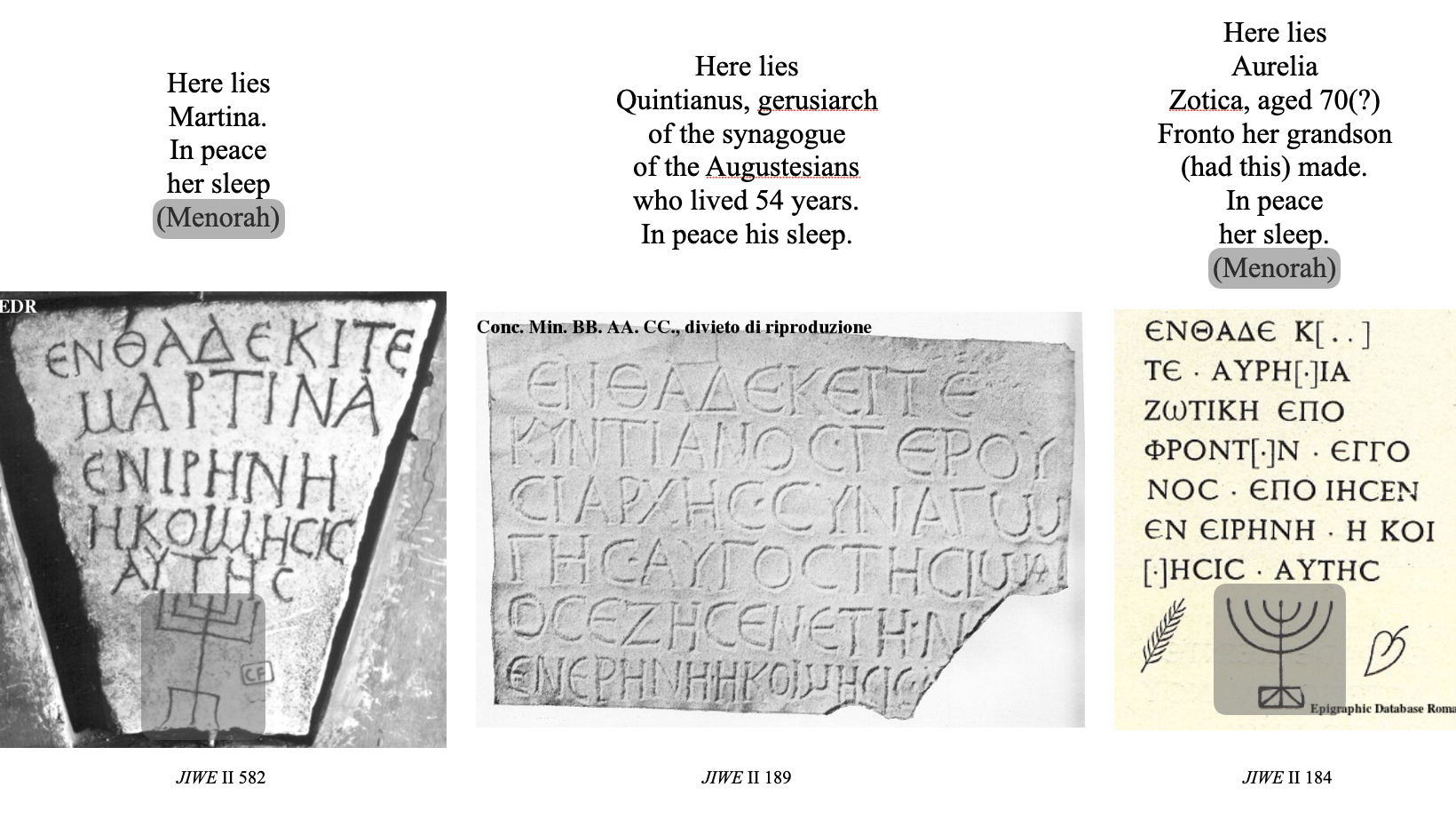

These Jewish inscriptions, almost all from the catacombs (underground cemeteries) in Rome, generally all start with the formula “Here lies”, “Ἐνθάδε κ(ε)ῖτε”, followed by the name of the deceased, and then the “in peace his/her/your sleep” formula. At the bottom, there may be a picture, most commonly a menorah.

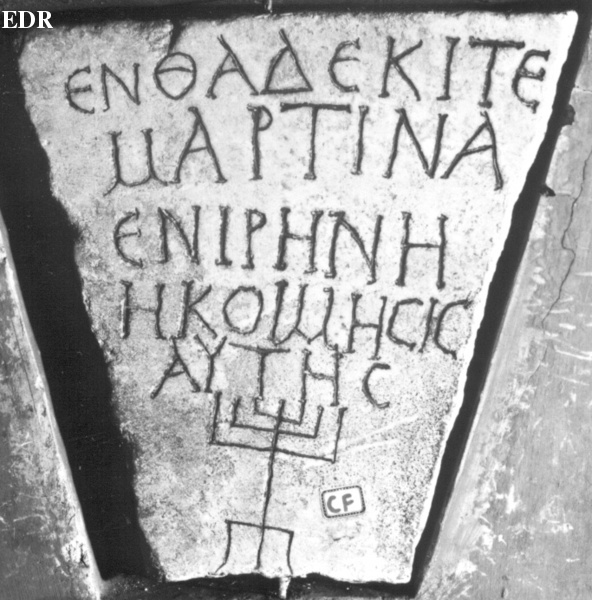

See the example below:

JIWE II 582

Ἐνθάδε κῖτε

Μαρτίνα·

ἐν ἰρήνῃ

ἡ κοίμησις

αὐτῆς

((:menorah))

Here lies

Martina.

In peace

her sleep.

Where the medieval Christian inscriptions begin “here in peace rests”, the Jewish ones begin “here lies”, and end in “in peace your sleep”.

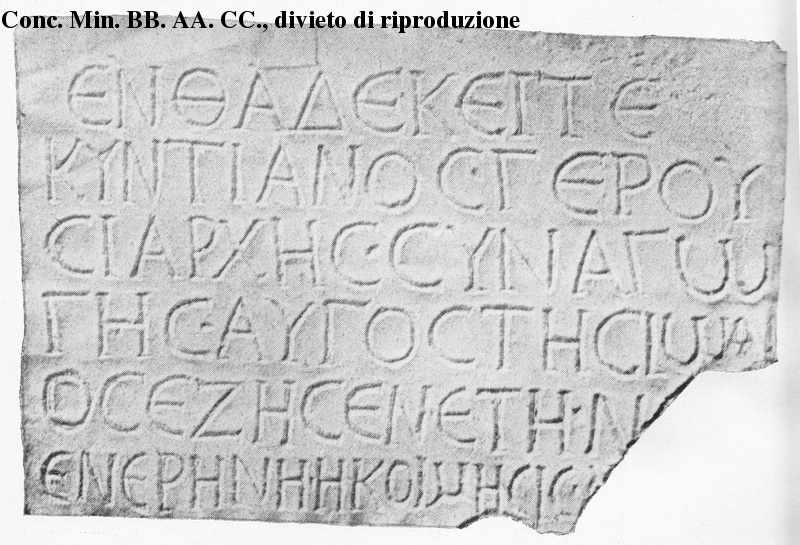

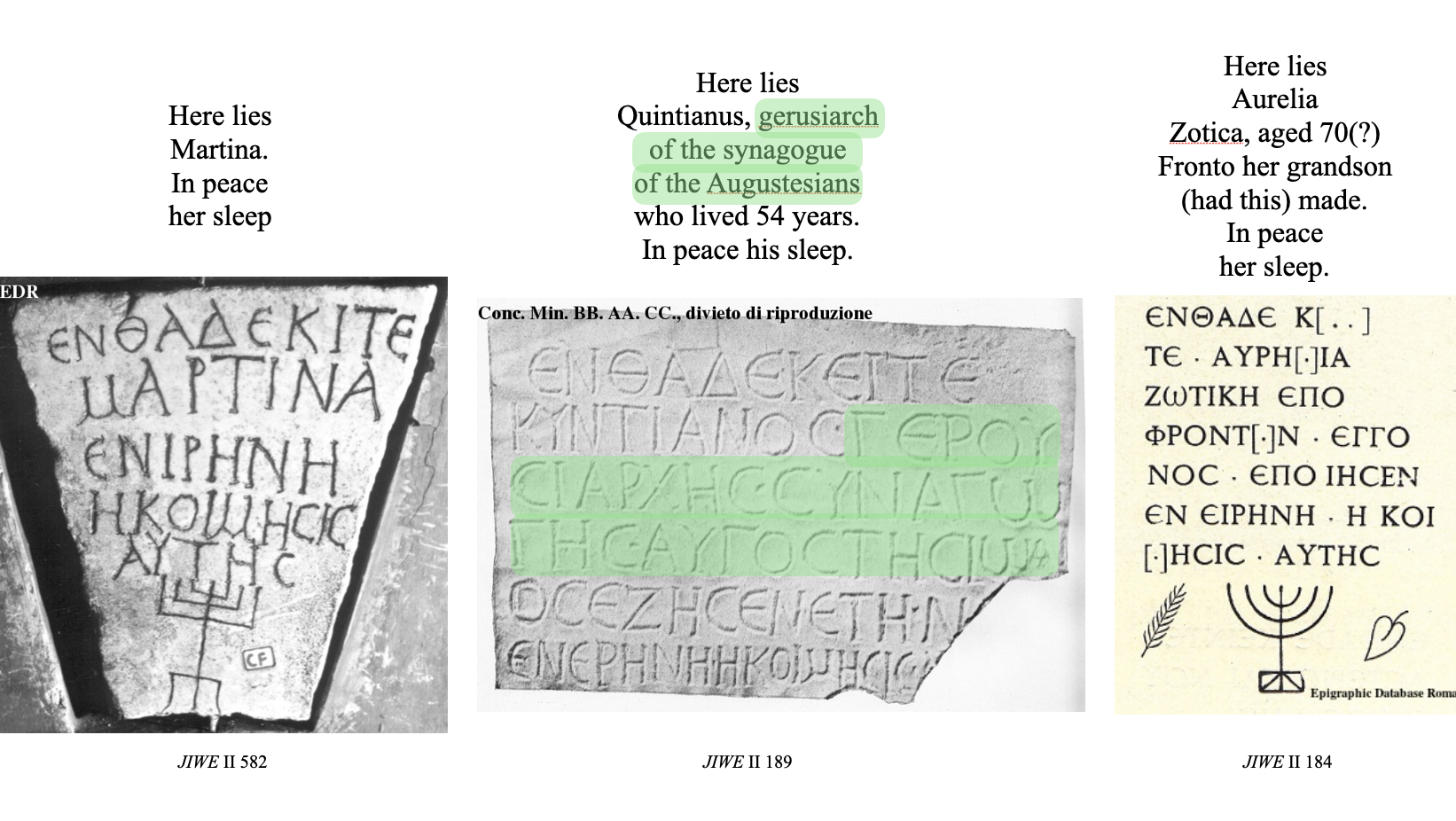

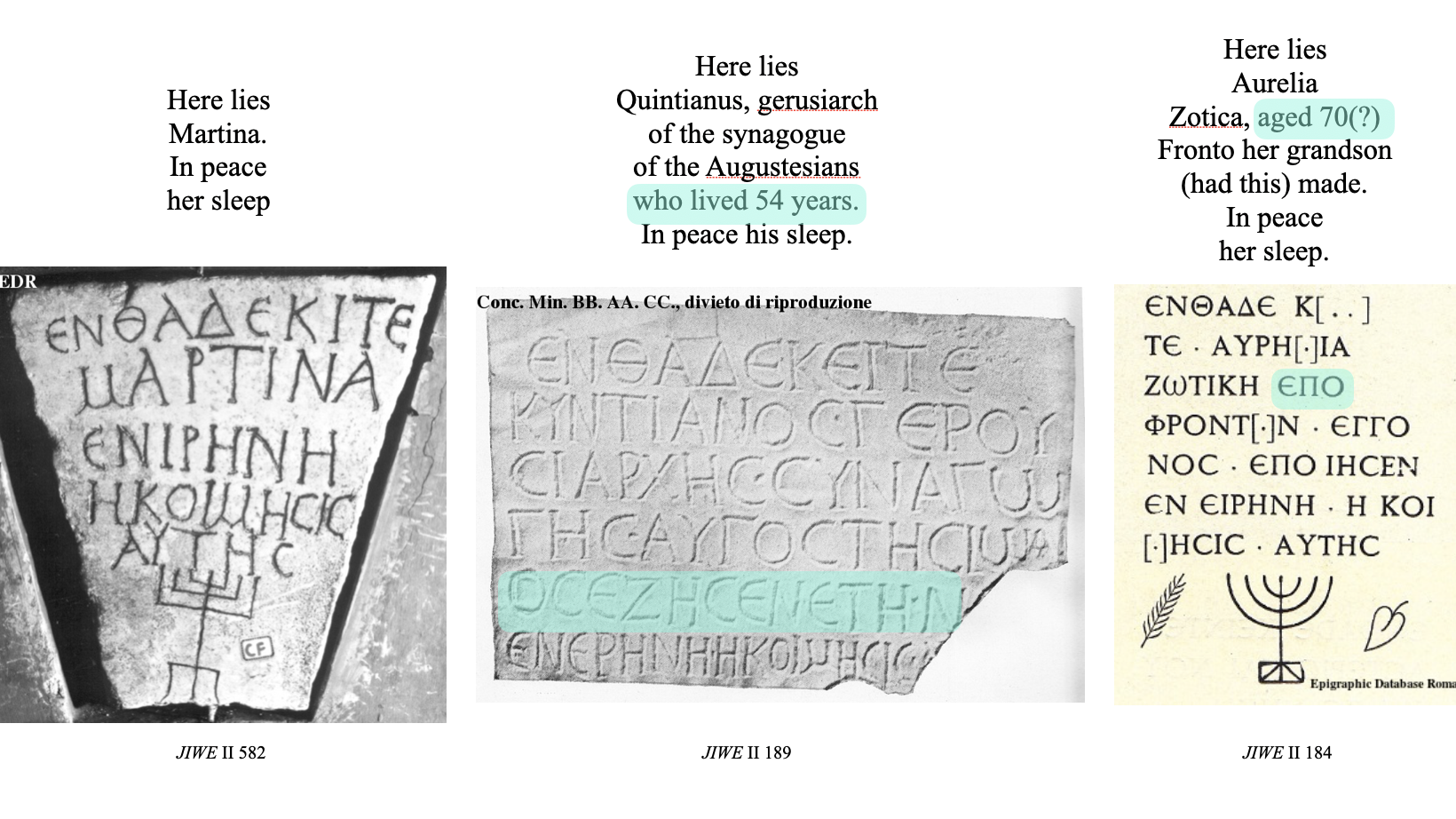

Sometimes inscriptions will have the role that the deceased held in the community, or their occupation, after their name. Their age may also be listed. Consider the example below:

JIWE II 189

Ἐνθάδε κεῖτε

Κυντιανὸς γερου-

σιάρχης συναγω-

γῆς Αὐγοστησίων(:Αὐγουστησίων)

ὃς ἔζησεν ἔτη ν[δʹ]˙

ἐν ἐρήνῃ(:εἰρήνῃ) ἡ κοίμησις α̣[ὐτοῦ].

Here lies

Quintianus, gerusiarch

of the synagogue

of the Augustesians

who lives 54 years.

In peace his sleep.

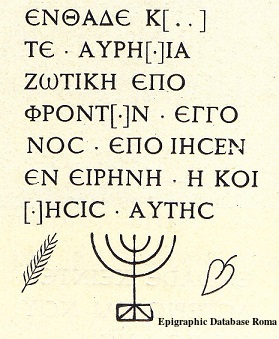

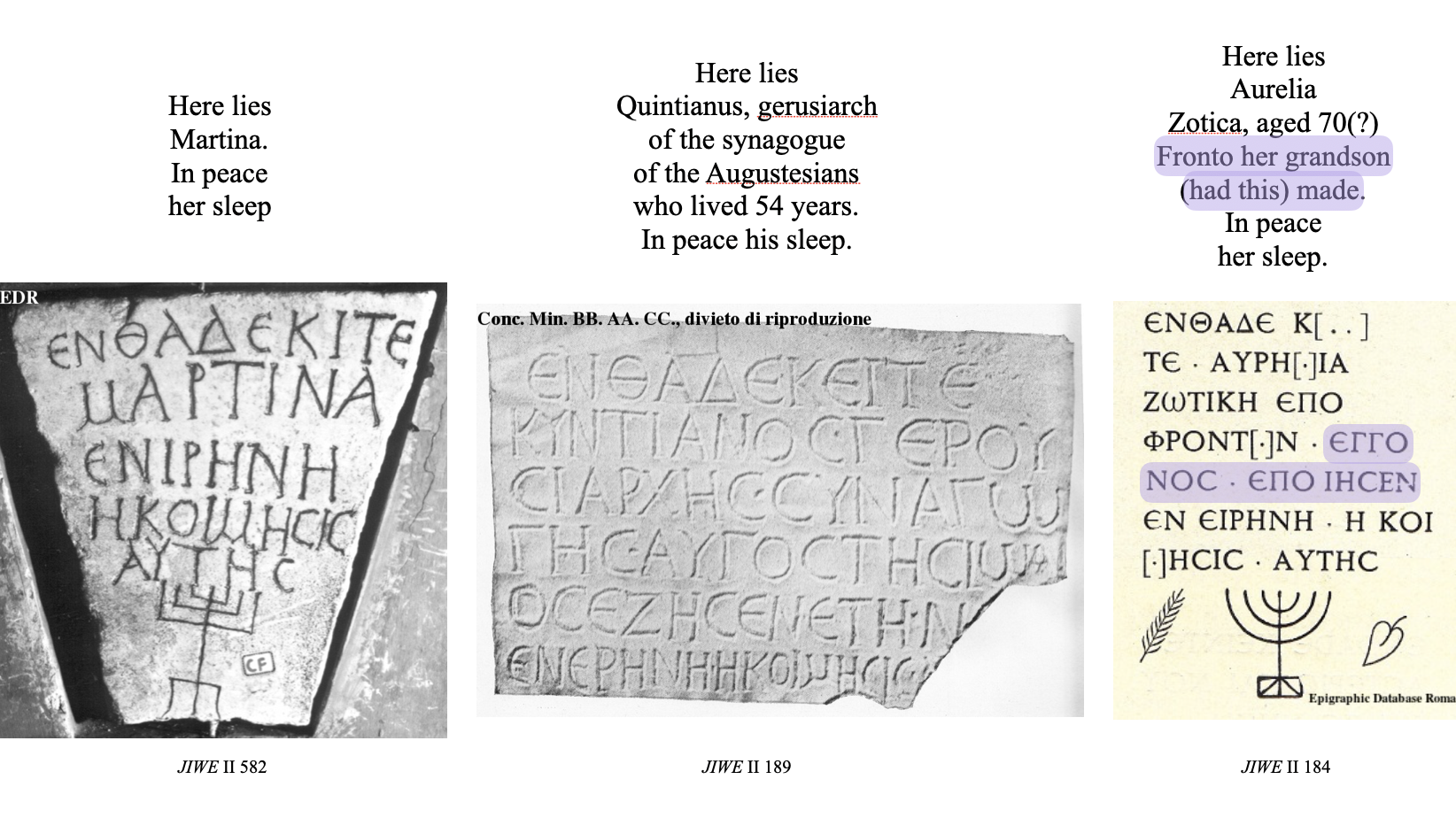

Sometimes the relationship between the deceased individual and the one who put up the inscription is declared. (The image for this inscription is based on a manuscript copy by an archaeologist, because the current location is unknown). Consider the example below:

JIWE II 184

Ἐνθάδε κ[εῖ]-

τε Αὐρη[λ]ία

Ζωτικὴ ἐπ(ῶν)(:ἐτῶν) ο´·

[Φ]ρόντ[ω]ν ἔγγο-

νος ἐποίησεν.

Ἐν εἰρήνῃ ἡ κοί-

[μ]ησις αὐτῆς

((:lulab?)) ((:menorah)) ((:ethrog))

Here lies

Aurelia

Zotica, aged 70(?)

Fronto her grandson

(had this) made.

In peace

her sleep.

With this in mind, we will further consider the formulae and function of phrases on inscriptions.

Inscriptions almost always start with an introductory phrase:

Then they usually have the name of the deceased:

Then perhaps they might introduce the role or occupation an indivdiual had:

They might state the age of the deceased:

They might mention the individual who paid for the inscription, or the individual who is mourning:

Most significantly for Jewish epitaphs from Rome, they will almost always have the closing formulae, "in peaace his/her/your sleep":

And finally, they might have some images, such as a menorah:

Considering the examples of formulae mentioned above, match the example formulae to the function.

When comparing Christian and Jewish inscriptions, they can be extremely similar. In this exercise, demonstrate the key markers of Jewishness in the epitaph.

Textual

Visual

To summarise:

- Inscriptions are highly formulaic texts.

- Certain patterns can help us quickly identify what kind of inscription it is, whether it be a war memorial, or a funerary epitaph.

- Jewish and Christian inscriptions of Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages share many elements and ideas, but have different forms.

With this in mind, we will now examine inscriptions which have other kinds of texts in them, beyond typical formulae. The formulae help us to identify an atypical text.