2. Common Elements of Inscriptions I

Inscriptions are generally very formulaic texts, and usually have set phrases that assists in identifying them. For example, most First World War memorials in England include “Lest We Forget”, which is part of the signifier of the inscription being a WW1 memorial.

WW1 memorial from Findhorn, Scotland

Inscriptions might also might have certain abbreviations, such as “S.”, “St.” or "Scs" for saints, or “AD” for “Anno Domini”, meaning in the common era. These abbreviations are, of course, used outside of inscriptions as well, but there are some abbreviations that mostly exist in inscriptions.

In particular, gravestones often have “RIP”, standing for “Rest In Peace”, from the Latin “requiescat/requiescit in pace”, which became ubiquitous on headstones during the eighteenth century. Although it is sometimes associated with Christian mass, it was used both on ancient and medieval Christian inscriptions.

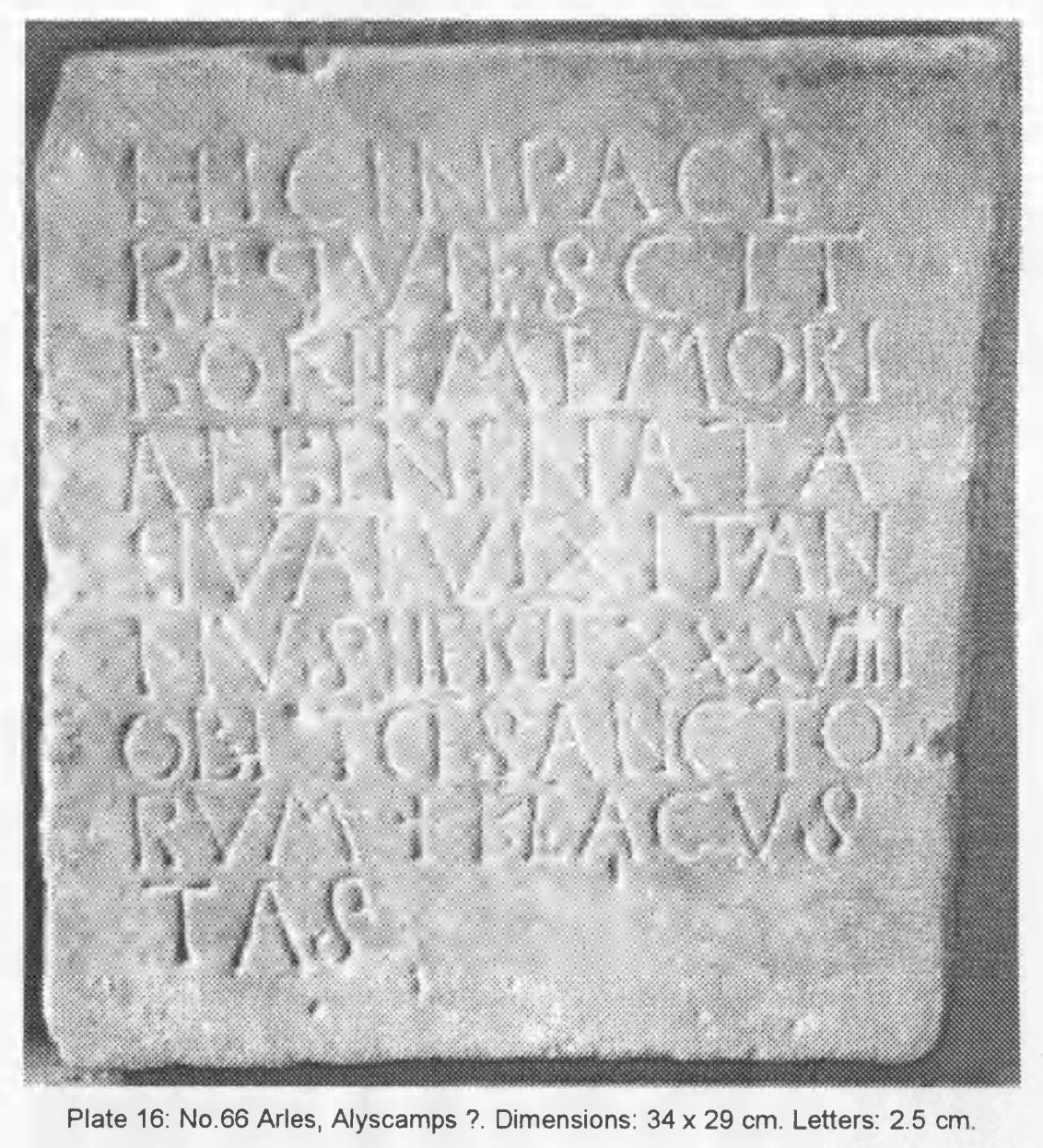

Many medieval Christian inscriptions begin with the phrase “here lies in peace in good memory”, often followed by the age of the deceased, and sometimes even when they died. Look at the Latin inscription below, from Arles in the South of France, probably from the fifth century CE.

SEG.66 = CIL.XII.941 = ILCV.2120

Hic in pace

requiescit

bone memori-

ae Benenata

quae vixit an-

nus II et di(es) XXXVIII.

Ob(i)t d(ie) sancto-

rum ((cross)) k(a)l(endas) agus-

tas.

Here in peace

rests,

of good memory,

Benenata

who lived

for two years and 38 days.

She died on the day of the saints

the first day of August.

Even without knowledge of Latin, you can observe from the “-” at the end of lines that words run on between lines. This is seen for “memoriae”, “annus”, and “sanctorum”. There are also not really spaces or dividers between words. To know where words begin and end, you have to already presume what would be written, or have excellent knowledge of Latin. Everything is also written in UPPER CASE.

If we render the text in the same way in English, it would look like this:

HEREINPEACE

RESTS

OFGOODMEMOR

YBENENATA

WHOLIVEDFOR2YE

ARSAND38DAYS

SHEDIEDONTHEDAYOFTHESA

INTSTHEFIRSTDAYOFAUGUST.

Furthermore, there are a few abbreviations used. In epigraphy, (brackets) are generally used to signify an expanded abbreviation. Instead of “RIP”, an epigrapher making an edition might write “r(est) i(n) p(eace)”. In the medieval inscription, “di” is written for “dies”, or “on the day”, and “kl” is written for “kalendas”, meaning “on the calends”, i.e. on the first day of the month, using the calendar system of the Roman calendar [in fact, the English word for “calendar” derives from “kalendae”!].

One could imagine a modern recreation like this:

HERERIP

OFGDMEMOR

YBENENATA

WHOLIVED42YE

ARSAND38DAYS

SHEDIEDONTHEDAYOFTHESA

INTSTHE1STDAYOFAUGUST.

Inscriptions usually have certain features that occur in a particular order.

Below we will see ((double brackets)) being used to represent an image on an inscription, while [square brackets] fill in words that aren’t there. For the Greek inscriptions we will encounter below, (:brackets with a colon) represent a correction to a non-standard spelling. {Curly brackets} delete letters that have been repeated by the scribe.

NB: Not every edition of inscriptions will use the same, but they will usually be some variation of this.

Abbreviations, capitalisation, lack of word dividers, and running on between lines are elements that can be seen throughout inscriptions, regardless of language, place or time, in the pre-modern world. We will look at a few more Latin Christian inscriptions, before examining some Greek Jewish ones, to solidify these concepts. By doing so, it will make it possible to utilise inscriptions more intimately, and explore the transmission of philological texts and ideas.

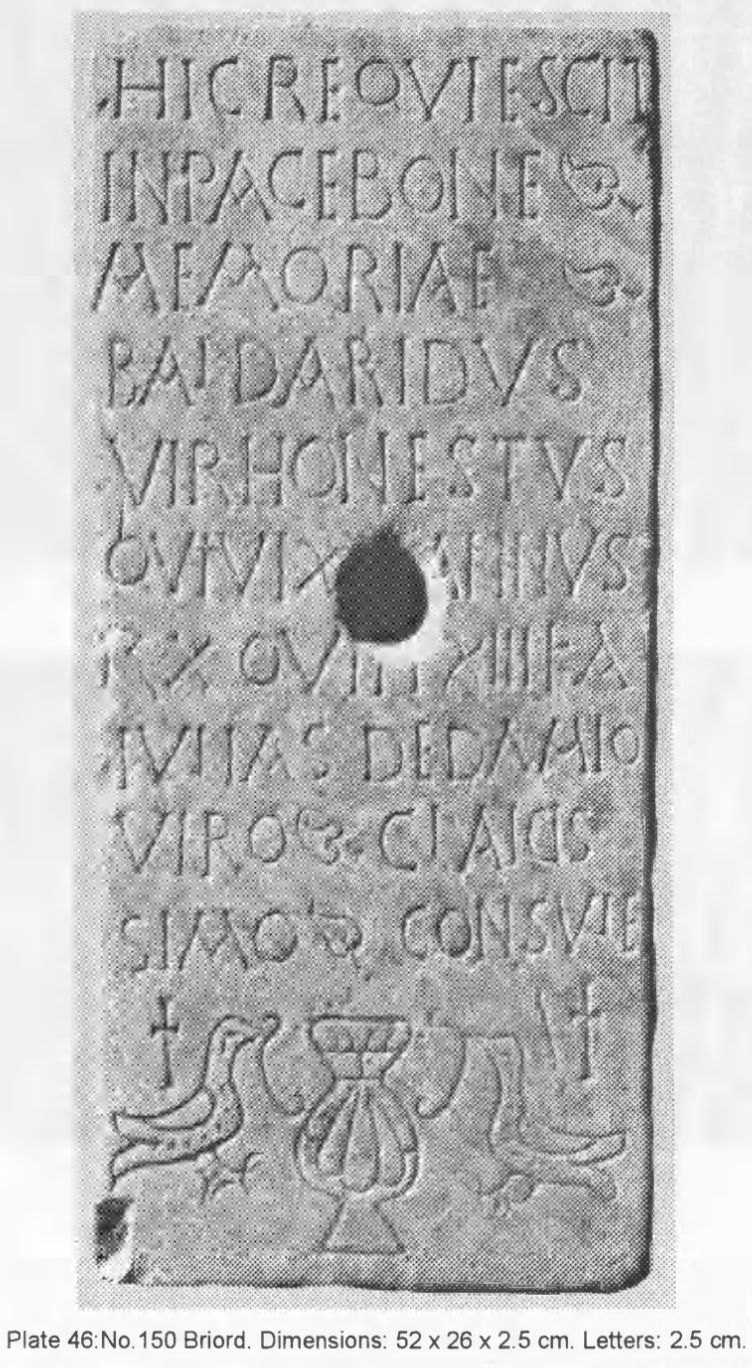

This inscription is from 19 June 488, from Briord, also in the South of France.

SEG 150 = CIL.XIII.2473 = ILCV.306

Hic requiescit

in pace bone ((ivy))

memoriae ((ivy))

Baldaridus,

vir honestus,

qui vix[it] annus

LX: oviit(:obiit) XII ka(lendas)

iulias, Dedamio

viro ((ivy)) cla(ri)s-

simo ((ivy)) consule.

((cross)) ((cross))

((dove)) ((vase)) ((dove))

Here rests

in peace, of good

memory,

Baldaridus,

an honest man,

who lived

70 years. He died on the 12 days before the kalends

of July [=19 June],

in the year of the consulate of Dynamius,

the most renouned.

Here we have the same “here rests in peace, of good memory [name] who lived [years, days]” formula, but with the addition of praise for the deceased -- “an honest man” -- and then the date of death. This inscription also is adorned with pictures!

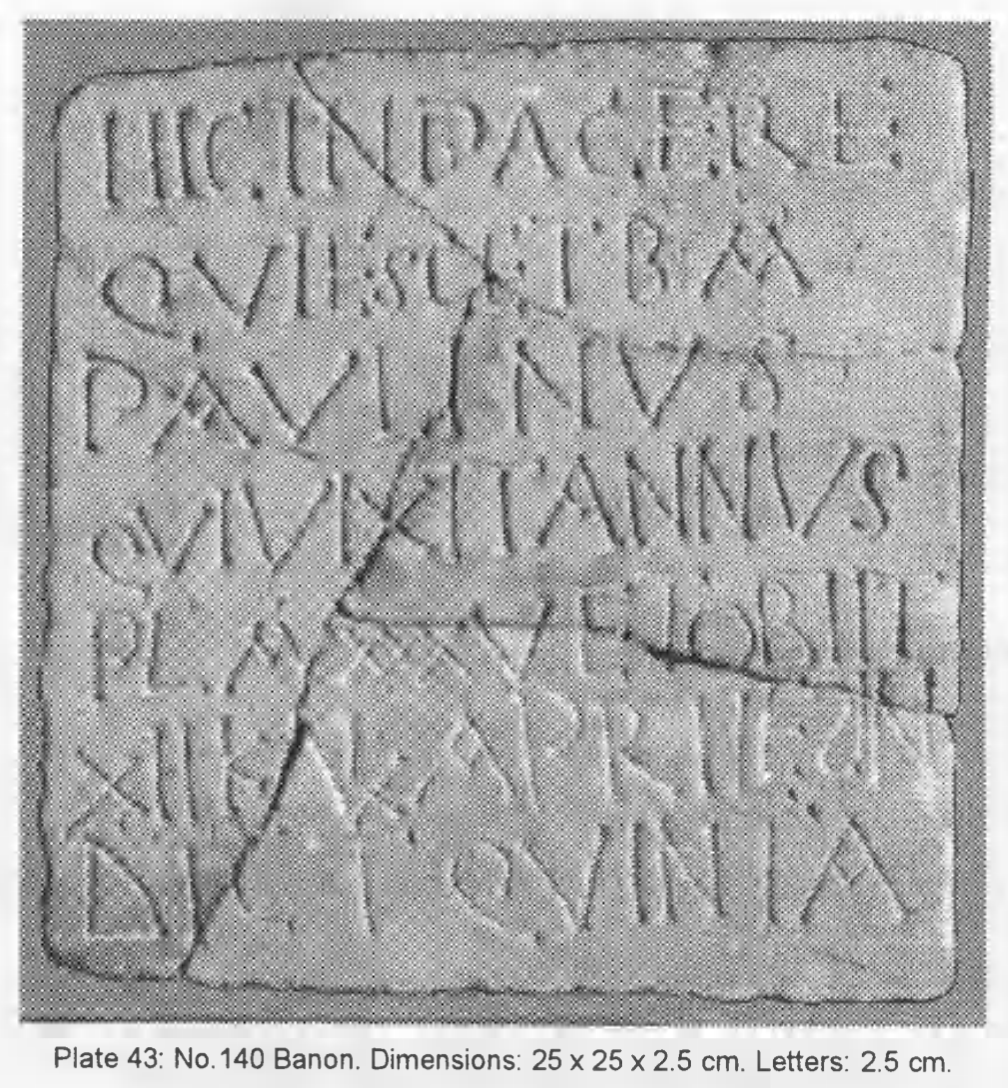

SEG 140 = ICMAMNS.62a

Hic in pace re-

quiescet b(onae) ((ivy)) m(emoriae)

Paulinus, ((ivy))

qui vixit annus

pl(us) m(inus) XXXV et obiit

XII kal(endas) apriles in-

dicti(one) quinta.

Here in peace

rests, of good memory,

Paulinus,

who lived for

more or less 35 years and died,

12 days before the kalends of April

in the fifth year of the indiction.

This inscription from Banon is from 21 March, but the year is unknown.

The above is very similar to the last two. Which differences can you spot?

Write in the box.

To summarise:

- Inscriptions are highly formulaic and use an number of abbreviations

- They cause difficulties for epigraphists who make editions with them, which relies on them using a number of punctuation marks to allow historians, philologists, and other scholars to work with them.

- [For example, ( ) expand abbreviations; (: ) indicate standardisations, and [ ] include words or letters that are missing.