Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy is the most widely transmitted (over eight hundred copies, including partial witnesses) and studied text of Italian literature. We do not possess either the autograph manuscript or the complete earliest phase of its transmission—indeed it would be more accurate to speak of “texts,” since the three canticles that make up the poem circulated independently of one another—because the oldest surviving witness (La) dates to 1336, fifteen years after the author’s death. The tradition is marked by extensive and endemic contamination, strongly influenced by horizontal transmission, probably reinforced by the ‘serial production’ undertaken in scriptoria to meet the huge demand for copies. As a result, the text presents an extraordinary number of variants, which makes it extremely difficult not only to establish the correct reading but even to determine with certainty which variety of the Italian vernacular (among the many then spoken across the peninsula) Dante actually employed.

This problem of textual variants was already perceived, around 1330, by the first known copyist of the poem, Forese Donati of S. Stefano in Botena, who in his subscription note (transcribed by Luca Marti in the Mart. codex, Biblioteca Braidense, Aldina AP XVI 25) lamented the high level of textual corruption. Nevertheless, thanks to the rigid structure of the hendecasyllable and terza rima, the Commedia does not require large-scale reconstruction ope ingenii. The Dante philologist, therefore, is mainly concerned with selecting among the variants and defining the linguistic form of the text.

In 2021, on the occasion of the 700th anniversary of the poet’s death, a new critical edition of the Commedia appeared as part of the National Edition of Dante’s Works promoted by the Società Dantesca Italiana. Almost simultaneously, another critical edition of the Inferno was published by a team directed by Paolo Trovato, and one should also mention Enrico Malato’s edition, which, although not strictly critical, proposes a revised text. Faced with this panorama of studies, one might think that Dante philology (understood here narrowly as philological work on the poet’s texts) no longer offers significant challenges. Nothing could be further from the truth. Work on the poem involves not only interventions for the text but also on the text. In other words, it is not limited to strictly textual matters: even choices of punctuation can decisively shape the text and therefore require interpretation in order to establish the constitutio textus.

For example, in Paradiso XXVII, 23–24, modern editions unanimously adopt a punctuation that creates an enjambment between the verb vaca and the phrase ne la presenza:

Quelli ch’usurpa in terra il luogo mio,

il luogo mio, il luogo mio che vaca

ne la presenza del Figliuol di Dio,

fatt’ ha del cimitero mio cloaca

del sangue e de la puzza; onde ’l perverso

che cadde di qua sú, là giú si placa

[He who on earth usurps my place, my place,

my place that in the sight of God’s own Son

is vacant now, has made my burial ground

a sewer of blood, a sewer of stench, so that

the perverse one who fell from Heaven, here

above, can find contentment there below]

Commentators have explained this as meaning that the papal seat is vacant before Christ, i.e. that Christ does not mystically guide the Church through the pope, not recognizing him as his vicar. The line is therefore interpreted as: the one (Boniface VIII) who usurps my place on earth—a place which, before the Son of God, is vacant—has turned my cemetery into a sewer of blood and stench. However, as I argued in a recent article (Ciarrocchi, 2024), the construction vacare + prepositional phrase with in (ne) is neither Dantean nor characteristic of Ancient Italian usage. In Dante’s vernacular works, the verb vacare appears only in the Commedia, four times and always in rhyme, with an absolute use. Three of these cases occur in the Paradiso, where the verb refers specifically to ecclesiastical offices in contexts criticizing the misgovernment of the Church (Par. XII 92; XVI 113; XXVII 23). In Ancient Italian, vacare is generally used of offices or charges, and when it governs in + noun, it means ‘to devote oneself to’ (e.g. vacare in certi studi). By contrast, in the sense of ‘to be empty, lacking,’ the verb appears only once in Paolino Pieri’s Cronica, and otherwise is always absolute, or with di/per, exactly as in Dante. On this basis, I have proposed changing the punctuation at Par. XXVII 23–24, placing a comma after vaca and removing the one after Dio:

Quelli ch’usurpa in terra il luogo mio,

il luogo mio, il luogo mio che vaca,

ne la presenza del Figliuol di Dio

fatt’ ha del cimitero mio cloaca

del sangue e de la puzza; onde ’l perverso

che cadde di qua sú, là giú si placa

[He who on earth usurps my place,

my place, my place that is vacant now,

in the sight of God’s own Son has made my burial ground

a sewer of blood, a sewer of stench, so that

the perverse one who fell from Heaven, here

above, can find contentment there below]

In this reading, vacare is used absolutely, in line with both Dante’s usage and Old Italian, and the text becomes more coherent. It also sharpens Dante’s daring polemic: the papal throne is vacant in absolute terms, while a living pope still occupies it. Before Christ’s eyes, the usurper has turned Peter’s sacred cemetery into a sewer.

Anyway, beyond strictly linguistic considerations, critical reading of the poem is indispensable, keeping them in a reciprocal relationship where each informs the other. In the case of Par. XXVII, the text itself appears to support this interpretation: Peter’s invective is aimed directly at the recent popes, contrasting their actions with those of his earliest successors. The “bride of Christ” (v. 39), the Church, was nourished by the blood of Peter, Linus, and Cletus, and by that shed by Sixtus, Pius, Callistus, and Urban (vv. 39–45), in stark contrast to the blood with which Boniface has made it a sewer (vv. 58–59). Peter denounces these successors (“i nostri successor,” v. 47), pointing to their abuse of the “keys” (v. 49), the papal insignia turned into a “banner” (v. 50), and the papal seal prostituted in false privileges (vv. 52–53). These are themes already present in earlier cantos against papal corruption (Inferno XIX, XXVII). In this final prophetic invective of the poem, Peter calls on Dante to bear witness openly: “and you, my son, who will return below / to the mortal burden, do not hide / what I do not hide” (vv. 64–66). The novelty of this passage lies precisely in the motif of the vacancy and usurpation of the papal seat, highlighted by the eclipse imagery (v. 36) and echoed in Beatrice’s words near the canto’s end (che ’n terra non è chi governi; / onde sí svïa l’umana famiglia ; vv. 140-141)). Details that reinforce the interpretation proposed above.

Much remains to be done both for and on the text of the Commedia, and the contribution of all is needed!

See: E. Ciarrocchi, Sul testo di Par., XXVII 23-24, in Rivista di studi danteschi (ISSN 1594-1000), 2024, 2, (doi: 10.60999/116970)

The first English translation is quoted from Digital Dante (https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/paradiso/paradiso-27/)

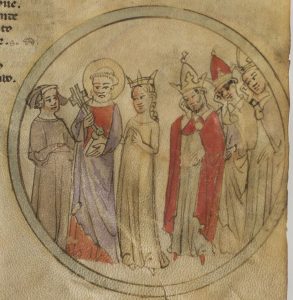

The First picture is from:

https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN647742837&PHYSID=PHYS_0188&DMDID=DMDLOG_0001

The second one from is from the Illuminated Dante Project:

https://www.dante.unina.it/idp/public/pagine/query/check/started/tabella/soggetti/id/777