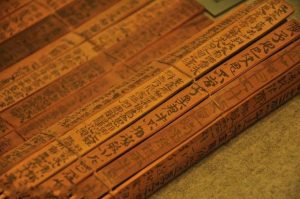

Fig. 1: A manuscript on bamboo slips (reproduction)

In ancient and imperial China, written culture was a major repository of wisdom and of high political and social relevance. Among the manifold intellectual streams revolving around textual traditions, beginning at least since the Hàn 漢 era (206 BCE ‒ 220 CE), the Five Classics (Wǔjīng 五經) became a paramount element of education and statecraft. Originally, Six Classics (or Six Skills, Liùyī 六藝) had been differentiated, but one of them, the Classic of Music, had long been lost. The remaining Five Classics encompassed the Odes (Shī 詩), Documents (Shū 書), Changes (Yì 易), Annals (Chūnqiū 春秋) and Rites (Lǐ 禮). Over time, each of these Classics came to consist of a tradition revolving around a canon of writings perceived of as sharing a tightly-knit relationship. For instance, the Rites Classic consists of three separate texts, which were regarded as informing one another. Texts written based on this canon, if they gained a sufficiently high status, could further expand the tradition. Besides the Five Classics, there were many other texts, but it was especially writings from among these traditions which were recognised and bolstered by the Hàn state, leading to their scholarship being institutionalised and used in the education and selection of civil servants. The Five Classics span a wide range of topics, from what we might call philosophy and history to literature and religion. The Chinese term “classic” (jīng 經) invokes the image of warp threads, the main threads in a piece of cloth. To provide but a glimpse into the relevance the Five Classics commanded in ancient Chinese scholarship, consider the following remark from the Explanations of the Classics (Jīngjiě 經解) Chapter in the Notes on Rites (Lǐjì 禮記):

“其為人也溫柔敦厚,《詩》教也。疏通知遠,《書》教也。廣博易良,《樂》教也。絜靜精微,《易》教也。恭儉莊敬,《禮》教也。屬辭比事,《春秋》教也。

If someone’s personality is gentle and genuine, they have been taught with the Odes. If they are incisive and understand even the remote past, they have been taught with the Documents. If they are broadly-learned and pleasant-natured, they have been taught with the Music. If they are refined and subtle, they have been taught with the Changes. If they are respectful and attentive, they have been taught with the Rites. And if they align their speaking with the real matters, they have been taught with the Annals.”

Each of the Classics had a different function and different contents, and yet they were often seen as intertwining. Studying them was a form of self-cultivation, making the learner worthy and able to rule "All under Heaven" (tiānxià 天下, i. e. the empire, nominally all the world) — or at least transform him into a better human. This is in part why the Classics were so esteemed by many scholars.

Philological practices dedicated to these Classics could involve compiling, copying, curating, transmitting, editing, disseminating, teaching, commenting on or writing about these texts. Writing developed to form the backbone of the empire’s power base and administration, but oral recitation, memorisation, and transmission presumably still played an important role because of how laboursome and resource-intensive it was to produce manuscripts. Before the spread of paper as a writing material between the second and fifth century, Chinese texts would mainly be written onto scrolls of tied-together bamboo slips or onto wood tablets, sometimes engraved into stone, sometimes written onto walls or silk fabrics. Commentaries were written to elucidate the classic texts.

Fig. 2: Reproduction of a bamboo manuscript

The perhaps most prominent early commentaries to the Five Classics are the traditions to the Annals (Chūnqiū, lit. Springs and Autumns). These Annals recount the history of the state of Lǔ 魯 in contemporary Shāndōng province. They were ascribed to Confucius (Kǒngzǐ 孔子, ca. 551‒479 BCE), thus supposedly containing the wisdom and thoughts of the renowned thinker, a towering figure over Chinese intellectual history. The Five Classics generally are sometimes called the “Confucian Classics”, and the scholars studying their thought and adhering to it are sometimes called “Confucians”, because virtually all Five Classics were associated with Confucius’ thought at some point. While the term has come in handy to distinguish what can otherwise only be roughly circumscribed as “classical” (a term which concurrent intellectual traditions such as Daoism and the writings associated with them would equally deserve), these scholars and the texts they studied and still study were only loosely based on Confucius’ thought.

In the case of the Annals, the assumed authorship of Confucius led to a problem: The Annals promised valuable insights into Confucius’ thinking and his view of his lifetimes and the world he lived in, but given the annalistic style, there are only very brief remarks for a given year. This gave rise to the assumption that Confucius must have purposefully chosen each character in the text to reveal a hidden meaning upon closer scrutiny. To seize these “big meanings in tiny words” (wēiyán dàyì 微言大義), the commentators contextualised and elaborated upon the events and stories they presumed to underlie the Annals, explicating what Confucius supposedly had meant.

Fig. 3: Confucius

While these commentaries to the Annals certainly somewhat embellished the classic to the extent that they border on narrative literature, the sprawling genre of commentary-writing fulfilled multiple different purposes. Commentarial culture may thus be seen as a particularly important practice of philological care for the texts and their survival and continued intelligibility and relevance. While there are weighty commentaries boldly advancing the commentator’s own ideas and readings of the Classics, others remained focused on transmitting the pronunciation or meaning of individual words, as the development of language threatened the sustained understandability of the text. When variants had entered the text or other versions surfaced, commentators sought to point them out and retain what they deemed the “correct” version of the text. As time went on, even sub-commentaries saw the light of day — commentaries commenting on commentaries rather than on “main texts” such as the Classics directly. Some functions of commentary can be gleamed from the name a commentator gave his work to make it identifiable in the stratigraphy of text within the tradition.

For example, a genre of commenting upon every single section or even sentence was named “section and sentence commentaries” (zhāngjù 章句). Henceforth, in biographies, individuals’ personalities were sometimes characterised based upon whether or not they “adhered to the sections and sentences” (shǒu zhāngjù 守章句). The term had thus become synonymous with a meticulous, albeit somewhat pedantic and long-winded way of working with texts.

A famous late Hàn commentator named Zhèng Xuán 鄭玄 (127‒200) coined the designation zhù 注 for his commentaries (the variant zhù 註 subsided), which literally means “to pour in” or “to fill in”, fitting his somewhat terse style of short annotations.

In the Táng 唐 era (618‒907), an edition project led by Kǒng Yǐngdá 孔穎達 (574‒648) added commentaries named “correct meanings” (zhèngyì 正義) to several Classics.

Given that the texts the commentators worked on had emerged in the past, an important challenge they faced was to salvage the knowledge contained in the texts and passing it on whilst simultaneously advancing their own re-readings. Many scholars assumed that the Five Classics reflected bygone eras of great cultural heroes, whose virtuous governments had achieved “greatest peace” (tàipíng 太平). They conceived of ancient Chinese history as a story of increasing sophistication and cultural advancements at first, followed by periods of decay and crisis — in one word: disorder (luàn 亂). This disorder was partly attributed to the fact that the wisdom of antiquity had become tarnished with later distortions, as well as many losses of source materials. To scholars of the “Confucian” Classics, the first imperial dynasty preceding the Hàn, the Qín 秦 (221‒206 BCE) presented a pivotal rupture, separating them even more from the enlightened past. The Qín government, famously known for the First August Emperor of Qín (Qín Shǐ Huángdì 秦始皇帝, 259‒210 BCE) and his terracotta army, was accused of having practised harsh laws and militarisation, and of having oppressed the opposing voices of classical scholars advocating values gleamed from the Classics - such as benevolence (ren 仁), righteousness (yì 義), rites (lǐ 禮), or trustworthiness (xìn 信). Allegedly, the Qín burnt “Confucian” books and even executed “Confucian” scholars. While this is probably only partly true, and the succeeding Hàn adopted most of Qín’s institutions and laws, as well as the idea of a technocratic, centralised bureaucracy, it is important to understand the impetus such collective ideas had on classical scholarship: A sort of almost “archaeological” or “reconstructive” philology and explanations through commentaries were often deemed necessary means to re-establish the “original meanings of the former sages” (xiānshèng zhī yuányì 先聖之原意), attempting to undo the losses and adulterations resulting from the preceding ages and contemporaries’ errors.

Fig. 4: A depiction of a teaching scene in the Hàn Great Academy (tàixué 太學) on a tile

Commentaries were not the only way to accomplish this. Classical philological practices surrounding the Classics often started with compiling the texts. Individuals also wrote essay-like independent texts expounding their opinions. There were even congresses held by some emperors to discuss the role and trajectory of certain Classics (the most famous example being the meeting in the White Tiger Hall, Bóhǔ tóngyì 白虎通議). Another example are dictionaries or encyclopaedias such as the Elucidations of Writing Patterns and Explanation of Graphs (Shuōwén jiězì 説文解字), a sort of early dictionary. Its purpose was to clarify the supposed original meaning of the characters used in all sorts of texts, such as the Five Classics. The underlying idea was to aptly represent reality in writing (zhèngmíng 正名, lit. "rectifying the denominations"). If this reality was understood well, thus the theory, this understanding could be implemented to bring the right order to All Under Heaven. For example, the character wén 文 ("writing pattern", or simply “text”) is defined in the Shuōwén as “[…] criss-crossing strokes. They are patterns of merging shapes. 文,錯畫也。象交文。” The Shuōwén jiězì also explains the pronunciation of characters, and frequently touches upon etymology to delineate the shape of the character. These forms of engagement with the texts, together with the commentaries, provided the framework through which scholars attempted to approach texts to approximate their meaning and make sense of them, whilst also conserving them and transmitting them to posterity as safely as possible.

Many readers of the Classics and the commentaries may have been students. Studying the classics became an integral part of education. They were also an integral part of the civil service examinations since the Hàn period. In other words, knowledge of the Classics was a prerequisite to taking office in the higher echelons of imperial administration. On the other hand, large parts of the Classics focus on the person of the ruler first and foremost, reckoning that positive influences would radiate down from the apex if the ruler be virtuous and well-educated. The Documents (Shū) tradition, for instance, was considered to contain the deeds and sayings of venerated rulers of antiquity. They were seen as a blueprint for later rulers to model themselves on in their self-cultivation. But the values proposed by the Classics pervaded many more layers of Chinese society and beyond into especially contemporary Korea, Japan and Vietnam.

Commentaries could help to sediment the understanding of a given text, but also transmute its reading and redirect it. Given their own specific social and historical background, commentaries, too, could thus be of political and hermeneutic relevance, exceeding the more strictly philological undertakings of curating the text by far. But given the devotion to the authority inherent to texts, and how eagerly wisdom and power were located in or affixed to texts, one could equally make the point that a philological devotion to the written word prevailed much of early imperial society (beginning from 221 BCE).

Of course, how to understand and interpret the texts was object to intellectual contention. Commentators, through every one of their annotations, voiced their own opinion, which impacted the interpretation of a given passage even if the commentator's remark was not explicitly interpretative. The commentators thus often took a distinctively personal, sometimes even resolutely idiosyncratic stance. Historically, Chinese texts had not been as expressly connected to the person of the author, but rather to the progenitor of the ideas voiced in a given text or the scribes jotting them down and transforming them into texts later. In a sense, the early imperial era thus saw the emergence of individuals giving their opinions on texts. Hitherto, this had been avoided, for Confucius was believed to have stated he himself had only served as a transmitter, not as a creator himself (shù ér bù zuò 述而不作). In the same way, commentators would still ostentatiously claim they were merely reversing the errors later transmitters or scribes had brought into the originally perfect text or based themselves on other authoritative texts to support their readings. Yet, commentaries did become a medium of scholarly debate. The fact that their commentaries present themselves as conceptually attached to a Classic rather than as standing for themselves, may likewise be seen as assuming a habitus of auxiliaries to the "main text" rather than as individual acts of authorship. Similar to scholastic glosses in medieval European liturgical texts, Chinese commentaries thus retained for themselves a status of "marginalia".

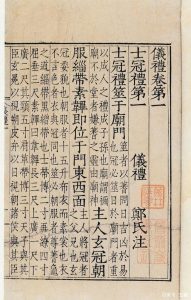

However, they could radically change the way a text would be perceived of. Once a commentary had reached a certain level of visibility, it became difficult to ignore. While commentaries often provided helpful aid to understand what the Classics say, what they mean became harder to determine without being influenced by what previous commentators had thought, whether one agreed or disagreed with them. At latest in the early modern period (i. e. the 11th to 12th century), it had become customary to arrange the commentary within the same written document, interspersing the lines of the "main text". The commentary now routinely intersected the "main text", for the sake of providing explanation just where it was needed. Still today, they thus mediate between readers and Classics. The most common editions of Chinese texts available for researchers today accumulate many different commentaries together with the "main text". Commentaries thus became an integral part of the tradition they originally were not much more than appendices to, serving both as powerful tools to keep the texts relevant and ensure their continued transmission and as distinct voices amidst the symphony of the classical canon.

Marco Pouget, 2023

Fig. 5: A printed Chinese text with the commentary inserted in smaller print.

Image sources:

Fig. 1: https://huaban.com/pins/2912356380 (19.4.23).

Fig. 2: https://k.sina.cn/article_2728618193_a2a368d1001001lee.html (19.04.2023).

Fig. 3: https://kxion.com/article/291.html (19.4.23).

Fig. 4: http://www.qulishi.com/news/201510/48399.html (19.4.23).

Fig. 5: https://baike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=e0a309bf6327197891c7b871 (19.4.23).

Test your knowledge!